During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a moratorium on evictions, recognizing that evictions could contribute to household and community spread of the disease.

However, the U.S. has little data on evictions to help experts understand where and why they occur, said Courtney Cronley, associate professor at the University of Tennessee, during a Monday APHA 2021 session on “Social and Community Context of Homelessness.”

The federal government provides a point-in-time count of people experiencing homelessness, but there’s no corollary assessment in the understanding of eviction, Cronley said.

In 2020, a team at Princeton University created the first dataset on evictions. Called the Eviction Lab, its data goes back to 2000. However, it relies on communities to input their data. In fact, Cronley discovered that Memphis was the only Tennessee city included in the Eviction Lab data.

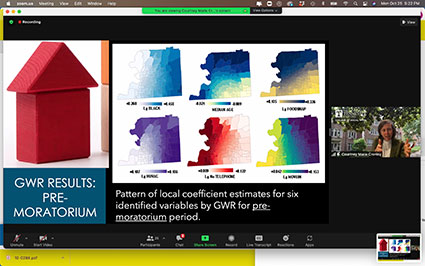

Cronley and her fellow researchers analyzed the Memphis data, looking for eviction clusters and racial disparities. They selected 28 predictive variables from the 2019 American Community Survey. Besides race, ethnicity and income, they also included the number of households in one location, those with no vehicle, commute time, household unit vacancy, lack of internet access, no phone and move-in date.

Researchers were able to map out clear hot and cold clusters in Memphis of evictions pre-moratorium; the areas shifted slightly during the moratorium in the fall of 2020. Being Black was a strong predictor of evictions.

Researchers were able to map out clear hot and cold clusters in Memphis of evictions pre-moratorium; the areas shifted slightly during the moratorium in the fall of 2020. Being Black was a strong predictor of evictions.

“Evictions are not randomly distributed; we’re seeing very strong cluster patterns, and those cluster patterns are strongly predicted by race, even when controlled for other factors that people commonly associate with evictions,” Cronley said.

To prevent evictions, communities need to consider geographically driven interventions and triaging resources to the areas of highest risk, she said.

“It is critical that we bring into the conversation structural racism,” she told attendees. “It seems highly likely, given that we’ve controlled for other factors associated with eviction…that there is probably structural racism at play, discriminatory treatment of Black tenants that places them at higher risk.”

She highlighted a few policies that hold promise in reducing eviction rates, including using eviction court navigators, providing tenant rights education, creating eviction diversion programs, and implementing data-driven policymaking and transparency.

Another presentation during the APHA 2021 session illustrated the disproportionate rates of homicide among people experiencing homelessness.

In a study of homicides in 15 states over 13 years (2005-2017), researchers discovered that people experiencing homelessness had an 11.8-fold greater risk of dying by homicide. The data, which was taken from the National Violent Death Reporting System, included 52,584 homicide victims who had housing and 798 victims without housing at the time.

There was a lot of variance among the states, with the highest risk in the U.S. Northwest, West and Southwest. When compared to housed victims, victims who were experiencing homelessness were slightly older, less likely to have emergency medical crews at the scene of death, and less likely to make it to an emergency room. Prostitution was also strongly associated with homicides among those experiencing homelessness.

A history of mental health was over-represented in the population, while current mental health treatment provided some protective factor. In other words, people experiencing homelessness are more likely to have a need for mental health services but less likely to be getting the treatment they need.

“That alone stops me in my tracks," said presenter Ben King, clinical assistant professor at the University of Houston. “I don’t know if there’s a better way to define the gap in treatment than something like that.”

Photo by Melanie Padgett Powers